Hreat. When hundreds of them can be harnessed to AI technology, they will become a tool of conquest.

By Elliot Ackerman and James Stavridis

March 14, 2024 10:00 am ET

By Elliot Ackerman and James Stavridis

March 14, 2024 10:00 am ET

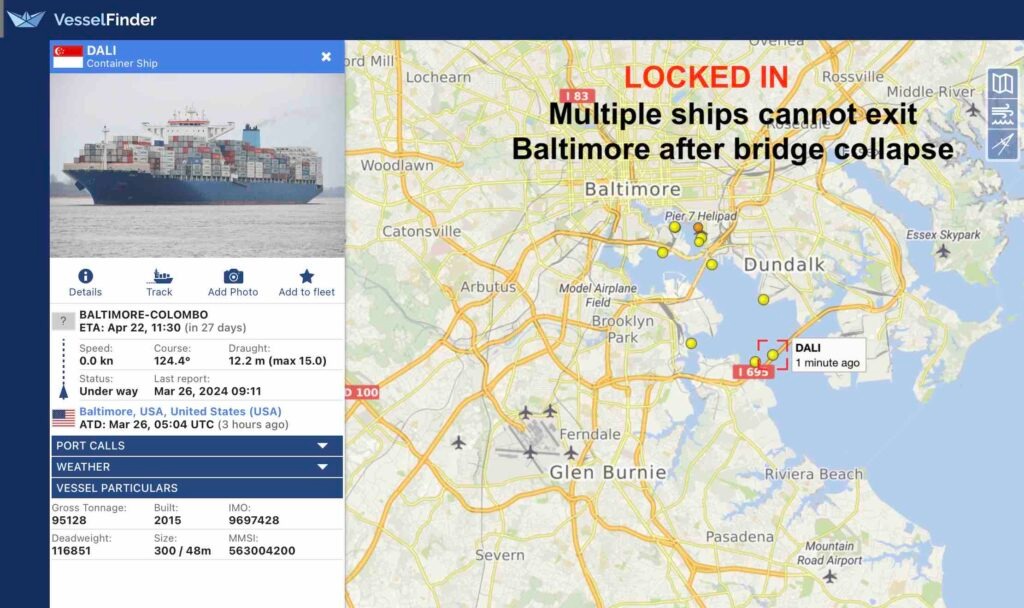

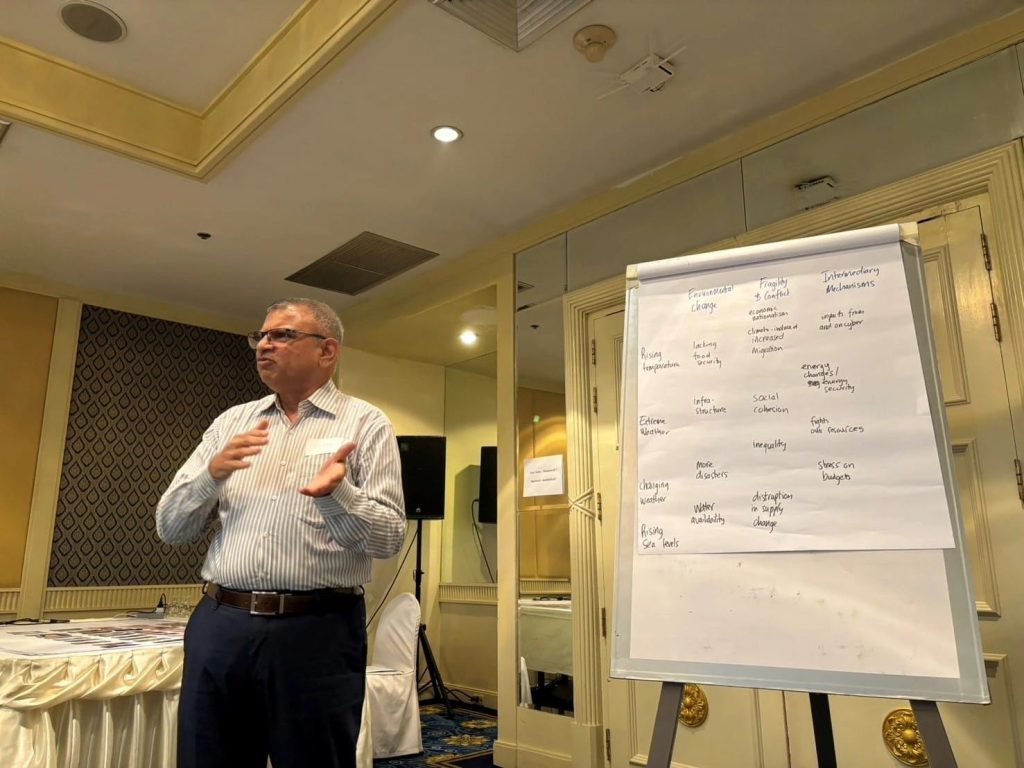

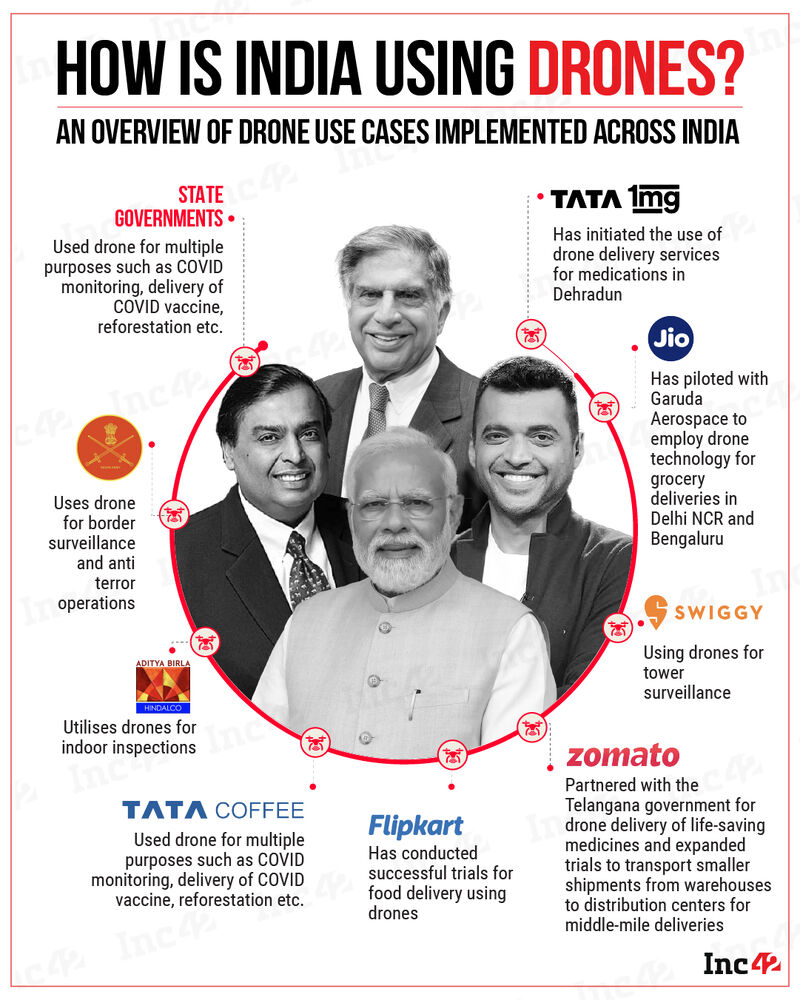

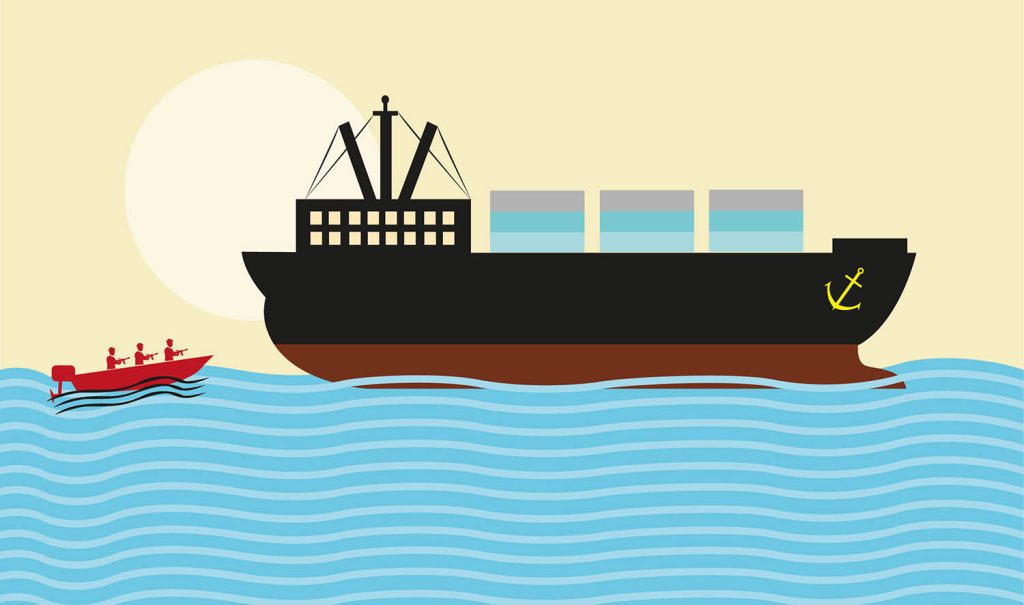

The Shahed-model drone that killed three U.S. service members at a remote base in Jordan on Jan. 28 cost around $20,000. It was part of a family of drones built by Shahed Aviation Industries Research Center, an Iranian company run by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. A thousand miles away and three days later, on the night of Jan. 31 into the morning of Feb. 1, unmanned maritime drones deployed by Ukraine’s secretive Unit 13 sunk the $70 million Russian warship Ivanovets in the Black Sea. And for the past several months, Houthi proxies have shut down billions of dollars of trade through the Gulf of Aden through similarly inexpensive drone attacks on maritime shipping. Drones have become suddenly ubiquitous on the battlefield—but we are only at the dawn of this new age in warfare.

This would not be the first time that a low-cost technology and a new conception of warfare combined to supplant high-cost technologies based on old ways. History is littered with similar stories. A favorite comes from the time of Alexander the Great. His conquests are as much a technological story as a political one. When Alexander’s army stepped onto the battlefield it was not only with a new technology—the sarissa, a 16-foot spear—but also with a new conception of how to use that weapon in tight, impregnable phalanxes. These heavily armed formations allowed Alexander to repel Persian armored chariots and Indian war elephants and to march deep into the subcontinent.

The phalanx armed with long spears was a military innovation that transformed ancient warfare, enabling the conquests of Alexander the Great.

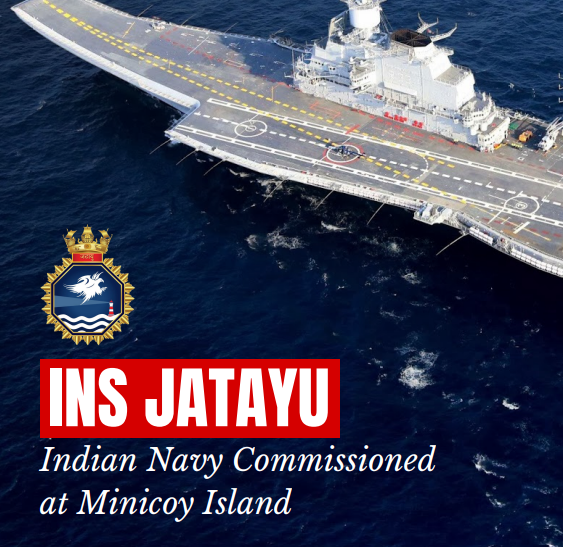

The most formidable element of American power-projection has long been the warship. After the Oct. 7 attacks against Israel, the Biden administration sent two carrier battle groups to the region to deter Iranian aggression. One of those carriers, the USS Gerald R. Ford, was on its maiden voyage, having recently been completed at a price tag of $13 billion. This makes it the most expensive warship in history.

For that same sum, a nation could purchase 650,000 Shahed drones. It would only take a few of those drones finding their target to cripple and perhaps sink the Ford. Fortunately, the Ford and other U.S. warships possess ample missile defense systems that make it highly improbable that a few, or even a few dozen, Shahed drones could land direct hits. But rapid developments in AI are changing that.

Drones are simple, cheap and available to militaries the world over—they’re the sarissas of today. But what those militaries have yet to achieve is the conception of war that will fulfill the potential of these unmanned systems. Much as the sarissa changed the face of warfare 2,000 years ago when employed in a phalanx of well-trained soldiers, the drone will change the face of warfare when employed in swarms directed by AI. This moment hasn’t yet arrived, but it is rushing to meet us. If we’re not prepared, these new technologies deployed at scale could shift the global balance of military power.

The future of warfare won’t be decided by weapons systems but by systems of weapons, and those systems will cost less. Many of them already exist, whether they’re the Shahed drones attacking shipping in the Gulf of Aden or the Switchblade drones destroying Russian tanks in the Donbas or smart seaborne mines around Taiwan. What doesn’t yet exist are the AI-directed systems that will allow a nation to take unmanned warfare to scale. But they’re coming.

A few Shahed drones are mostly a hassle, easily swatted from the sky except in the rare case when they score a lucky hit. They are best at blinding radars, disrupting communications and attacking small numbers of troops, as they did tragically in Jordan. But dozens or hundreds of drones in AI-directed swarms will have the capacity to overwhelm defenses and destroy even advanced platforms. Nations that depend on large, expensive systems like aircraft carriers, stealth aircraft or even battle tanks could find themselves vulnerable against an adversary who deploys a variety of low-cost, easily dispersed and long-range unmanned weapons.

Small inexpensive “off the shelf” drones like those Ukraine is using against Russia, and Hamas is deploying against Israel, are transforming modern warfare. To train American soldiers to counter this threat, the U.S. military recently opened a specialized drone warfare school.

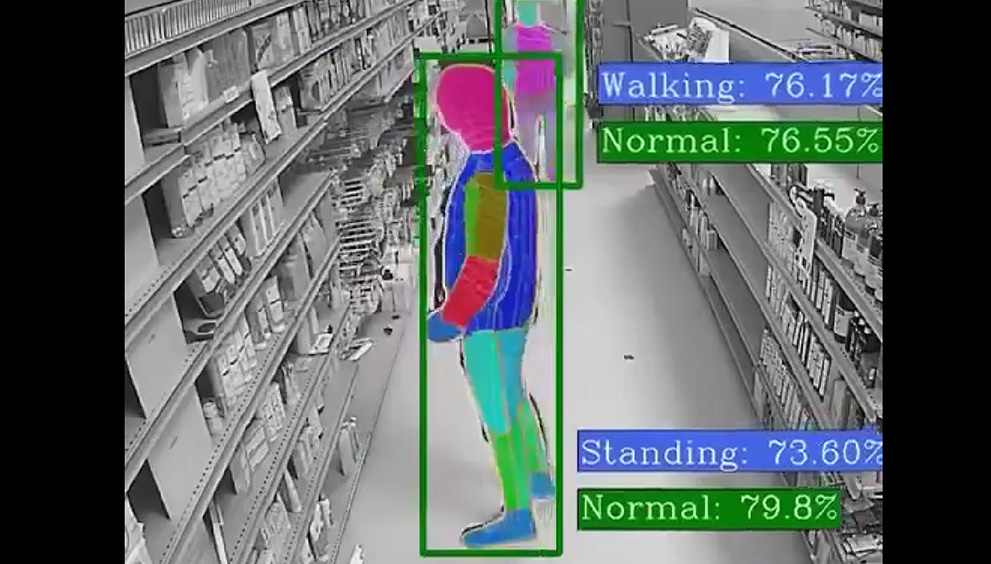

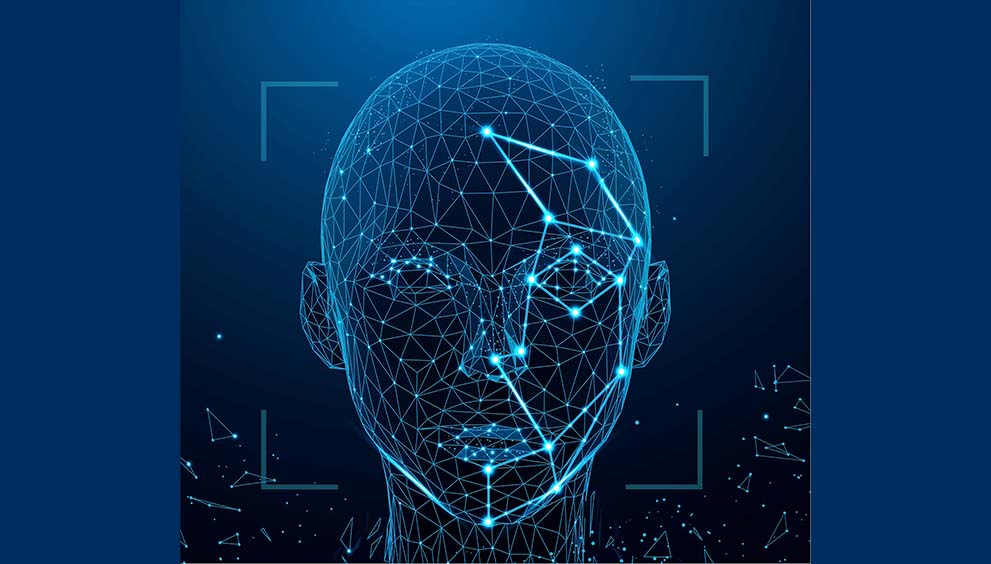

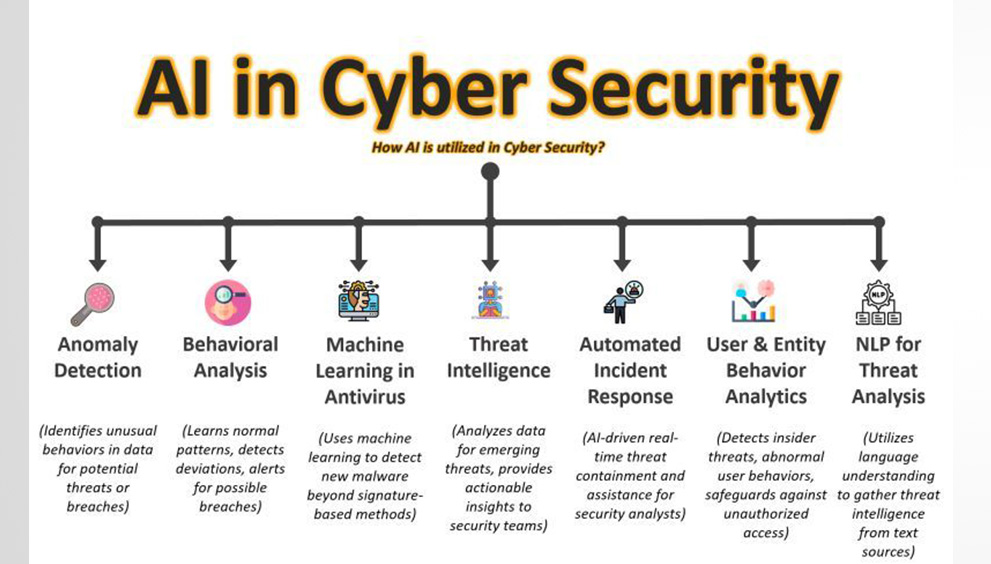

At its core, AI is a technology based on pattern recognition. In military theory, the interplay between pattern recognition and decision-making is known as the OODA loop—observe, orient, decide, act. The OODA loop theory, developed in the 1950s by Air Force fighter pilot John Boyd, contends that the side in a conflict that can move through its OODA loop fastest will possess a decisive battlefield advantage.

For example, of the more than 150 drone attacks on U.S. forces since the Oct. 7 attacks, in all but one case the OODA loop used by our forces was sufficient to subvert the attack. Our warships and bases were able to observe the incoming drones, orient against the threat, decide to launch countermeasures and then act. Deployed in AI-directed swarms, however, the same drones could overwhelm any human-directed OODA loop. It’s impossible to launch thousands of autonomous drones piloted by individuals, but the computational capacity of AI makes such swarms a possibility.

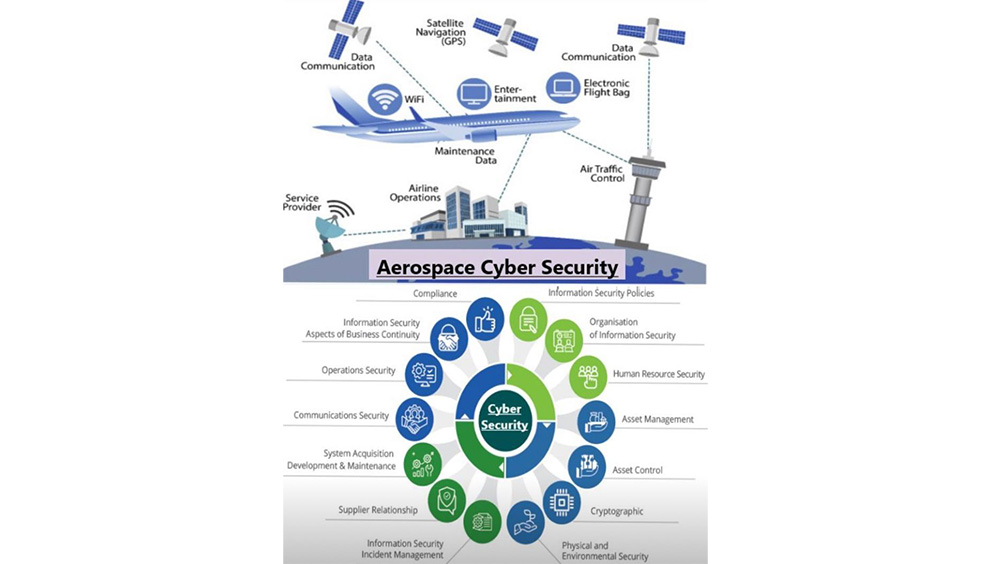

This will transform warfare. The race won’t be for the best platforms but for the best AI directing those platforms. It’s a war of OODA loops, swarm versus swarm. The winning side will be the one that’s developed the AI-based decision-making that can outpace their adversary. Warfare is headed toward a brain-on-brain conflict.

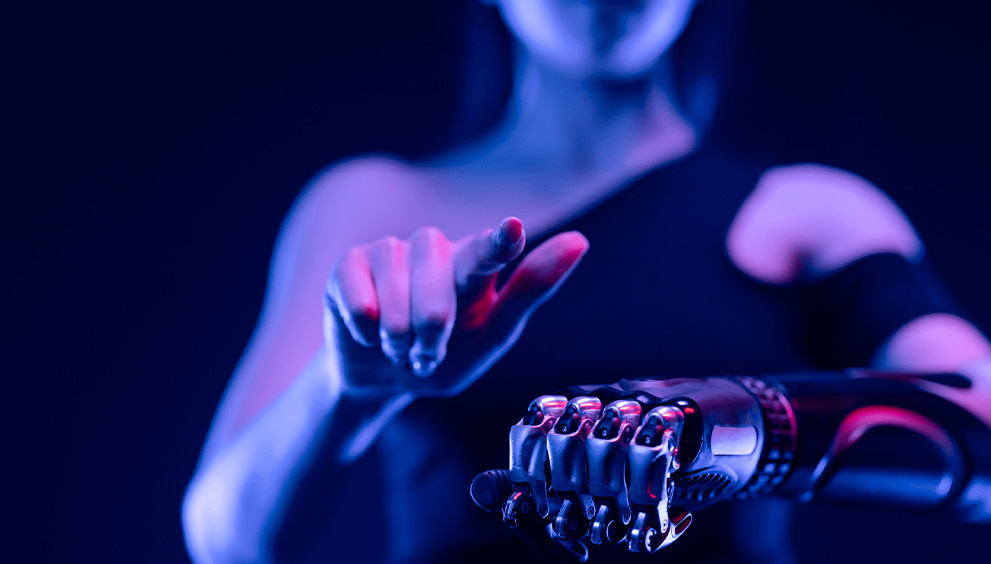

The Department of Defense is already researching a “brain-computer interface,” which is a direct communications pathway between the brain and an AI. A recent study by the RAND Corporation examining how such an interface could “support human-machine decision-making” raised the myriad ethical concerns that exist when humans become the weakest link in the wartime decision-making chain. To avoid a nightmare future with battlefields populated by fully autonomous killer robots, the U.S. has insisted that a human decision maker must always remain in the loop before any AI-based system might conduct a lethal strike.

But will our adversaries show similar restraint? Or would they be willing to remove the human to gain an edge on the battlefield? The first battles in this new age of warfare are only now being fought. It’s easy to imagine a future, however, where navies will cease to operate as fleets and will become schools of unmanned surface and submersible vessels, where air forces will stand down their squadrons and stand up their swarms, and where a conquering army will appear less like Alexander’s soldiers and more like a robotic infestation.

Much like the nuclear arms race of the last century, the AI arms race will define this current one. Whoever wins will possess a profound military advantage. Make no mistake, if placed in authoritarian hands, AI dominance will become a tool of conquest, just as Alexander expanded his empire with the new weapons and tactics of his age. The ancient historian Plutarch reminds us how that campaign ended: “When Alexander saw the breadth of his domain, he wept, for there were no more worlds to conquer.”

Elliot Ackerman and James Stavridis are the authors of “2054,” a novel that speculates about the role of AI in future conflicts, just published by Penguin Press. Ackerman, a Marine veteran, is the author of numerous books and a senior fellow at Yale’s Jackson School of Global Affairs. Admiral Stavridis, U.S. Navy (ret.), was the 16th Supreme Allied Commander of NATO and is a partner at the Carlyle Group.

Copyright ©️2024 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8

Appeared in the March 16, 2024, print edition as ‘Drone Swarms Are About to Change the Balance of Military Power’.

By Elliot Ackerman and James Stavridis

March 14, 2024 10:00 am ET

The Shahed-model drone that killed three U.S. service members at a remote base in Jordan on Jan. 28 cost around $20,000. It was part of a family of drones built by Shahed Aviation Industries Research Center, an Iranian company run by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. A thousand miles away and three days later, on the night of Jan. 31 into the morning of Feb. 1, unmanned maritime drones deployed by Ukraine’s secretive Unit 13 sunk the $70 million Russian warship Ivanovets in the Black Sea. And for the past several months, Houthi proxies have shut down billions of dollars of trade through the Gulf of Aden through similarly inexpensive drone attacks on maritime shipping. Drones have become suddenly ubiquitous on the battlefield—but we are only at the dawn of this new age in warfare.

This would not be the first time that a low-cost technology and a new conception of warfare combined to supplant high-cost technologies based on old ways. History is littered with similar stories. A favorite comes from the time of Alexander the Great. His conquests are as much a technological story as a political one. When Alexander’s army stepped onto the battlefield it was not only with a new technology—the sarissa, a 16-foot spear—but also with a new conception of how to use that weapon in tight, impregnable phalanxes. These heavily armed formations allowed Alexander to repel Persian armored chariots and Indian war elephants and to march deep into the subcontinent.

The phalanx armed with long spears was a military innovation that transformed ancient warfare, enabling the conquests of Alexander the Great.

The most formidable element of American power-projection has long been the warship. After the Oct. 7 attacks against Israel, the Biden administration sent two carrier battle groups to the region to deter Iranian aggression. One of those carriers, the USS Gerald R. Ford, was on its maiden voyage, having recently been completed at a price tag of $13 billion. This makes it the most expensive warship in history.

For that same sum, a nation could purchase 650,000 Shahed drones. It would only take a few of those drones finding their target to cripple and perhaps sink the Ford. Fortunately, the Ford and other U.S. warships possess ample missile defense systems that make it highly improbable that a few, or even a few dozen, Shahed drones could land direct hits. But rapid developments in AI are changing that.

Drones are simple, cheap and available to militaries the world over—they’re the sarissas of today. But what those militaries have yet to achieve is the conception of war that will fulfill the potential of these unmanned systems. Much as the sarissa changed the face of warfare 2,000 years ago when employed in a phalanx of well-trained soldiers, the drone will change the face of warfare when employed in swarms directed by AI. This moment hasn’t yet arrived, but it is rushing to meet us. If we’re not prepared, these new technologies deployed at scale could shift the global balance of military power.

The future of warfare won’t be decided by weapons systems but by systems of weapons, and those systems will cost less. Many of them already exist, whether they’re the Shahed drones attacking shipping in the Gulf of Aden or the Switchblade drones destroying Russian tanks in the Donbas or smart seaborne mines around Taiwan. What doesn’t yet exist are the AI-directed systems that will allow a nation to take unmanned warfare to scale. But they’re coming.

A few Shahed drones are mostly a hassle, easily swatted from the sky except in the rare case when they score a lucky hit. They are best at blinding radars, disrupting communications and attacking small numbers of troops, as they did tragically in Jordan. But dozens or hundreds of drones in AI-directed swarms will have the capacity to overwhelm defenses and destroy even advanced platforms. Nations that depend on large, expensive systems like aircraft carriers, stealth aircraft or even battle tanks could find themselves vulnerable against an adversary who deploys a variety of low-cost, easily dispersed and long-range unmanned weapons.

Small inexpensive “off the shelf” drones like those Ukraine is using against Russia, and Hamas is deploying against Israel, are transforming modern warfare. To train American soldiers to counter this threat, the U.S. military recently opened a specialized drone warfare school.

At its core, AI is a technology based on pattern recognition. In military theory, the interplay between pattern recognition and decision-making is known as the OODA loop—observe, orient, decide, act. The OODA loop theory, developed in the 1950s by Air Force fighter pilot John Boyd, contends that the side in a conflict that can move through its OODA loop fastest will possess a decisive battlefield advantage.

For example, of the more than 150 drone attacks on U.S. forces since the Oct. 7 attacks, in all but one case the OODA loop used by our forces was sufficient to subvert the attack. Our warships and bases were able to observe the incoming drones, orient against the threat, decide to launch countermeasures and then act. Deployed in AI-directed swarms, however, the same drones could overwhelm any human-directed OODA loop. It’s impossible to launch thousands of autonomous drones piloted by individuals, but the computational capacity of AI makes such swarms a possibility.

This will transform warfare. The race won’t be for the best platforms but for the best AI directing those platforms. It’s a war of OODA loops, swarm versus swarm. The winning side will be the one that’s developed the AI-based decision-making that can outpace their adversary. Warfare is headed toward a brain-on-brain conflict.

The Department of Defense is already researching a “brain-computer interface,” which is a direct communications pathway between the brain and an AI. A recent study by the RAND Corporation examining how such an interface could “support human-machine decision-making” raised the myriad ethical concerns that exist when humans become the weakest link in the wartime decision-making chain. To avoid a nightmare future with battlefields populated by fully autonomous killer robots, the U.S. has insisted that a human decision maker must always remain in the loop before any AI-based system might conduct a lethal strike.

But will our adversaries show similar restraint? Or would they be willing to remove the human to gain an edge on the battlefield? The first battles in this new age of warfare are only now being fought. It’s easy to imagine a future, however, where navies will cease to operate as fleets and will become schools of unmanned surface and submersible vessels, where air forces will stand down their squadrons and stand up their swarms, and where a conquering army will appear less like Alexander’s soldiers and more like a robotic infestation.

Much like the nuclear arms race of the last century, the AI arms race will define this current one. Whoever wins will possess a profound military advantage. Make no mistake, if placed in authoritarian hands, AI dominance will become a tool of conquest, just as Alexander expanded his empire with the new weapons and tactics of his age. The ancient historian Plutarch reminds us how that campaign ended: “When Alexander saw the breadth of his domain, he wept, for there were no more worlds to conquer.”

Elliot Ackerman and James Stavridis are the authors of “2054,” a novel that speculates about the role of AI in future conflicts, just published by Penguin Press. Ackerman, a Marine veteran, is the author of numerous books and a senior fellow at Yale’s Jackson School of Global Affairs. Admiral Stavridis, U.S. Navy (ret.), was the 16th Supreme Allied Commander of NATO and is a partner at the Carlyle Group.

Copyright ©️2024 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8

Appeared in the March 16, 2024, print edition as ‘Drone Swarms Are About to Change the Balance of Military Power’.

Member Login

Member Login