A Fine Balance : The DPDA and Data Localization

A Fine Balance : The DPDA and Data Localization

By Cyril Shroff, Arun Prabhu, and others..

On November 18, 2022, when the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (“MEITY”) tabled an entirely new draft Digital Personal Data Protection Bill, 2022 (“Draft”)[1], the concerns around one section, namely Section 17 dealing with cross-border data transfers, were perhaps more pronounced than the shock which accompanied the withdrawal of a long debated previous draft.

The criticisms around this section which essentially required the Central Government (“Government”) to “whitelist” territories to which transfer of personal data[2] was permissible, revolved around two specific issues:

- Whether this approach would simply “break” global business processes by creating uncertainty around what was permissible until the notification; AND

- Given the purported overriding effect of the Draft,[3] whether transfer to a “whitelisted” location would be permissible in view of the extensive, sector specific, localization regime which is already applicable in India.[4]

As a part of our series of analysis on the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 (“Act”)[5], we now examine the revised approach to cross border data transfers under the Act, as well as some comparative global positions.

The Story So Far

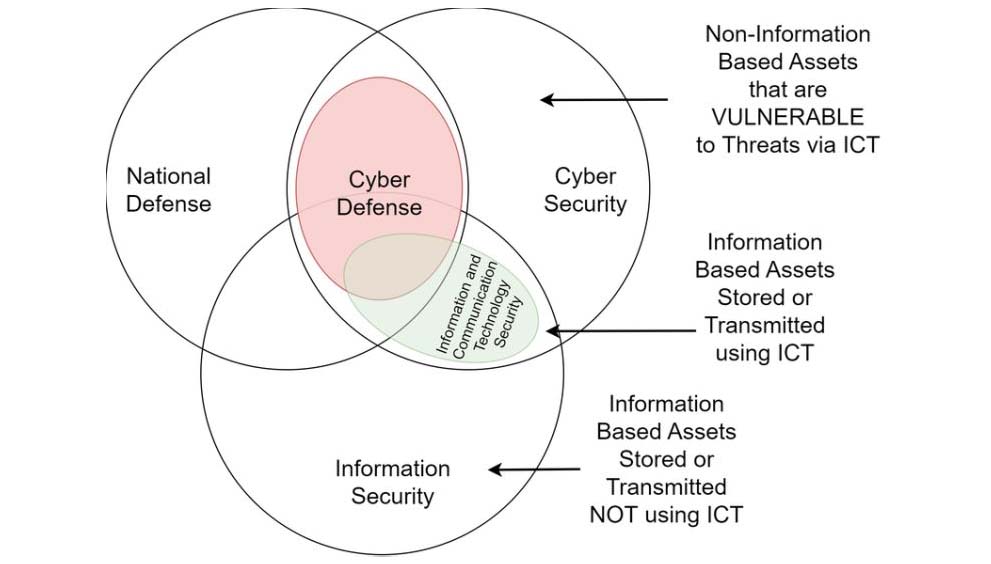

The conflict between the imperatives of data sovereignty and creating a “single market” to enable free data flows, is a conundrum that regulators globally have attempted to solve in different ways. Attempts leaning towards the former approach, like China’s great firewall,[6] and Russia’s data balkanization[7], have also demonstrated their negative impact on innovation and global competitiveness.[8]

Sadly, the most famous example of the “open” approach, Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (“GDPR”) is today, something of a cautionary tale. Between the disruption surrounding key international data flows through the Schrems decisions[9], and the multiple efforts to resolve them[10], there is a sense of palpable relief around what is hopefully, a sustainable international transfer framework under revised the standard contractual clauses.[11]

In a global socio-economic context where data (and by natural extension, innovation in areas such as AI and Big Data) is increasingly recognized as a strategic game changer, India, as a key stakeholder which also bears the responsibility of global leadership, had to find a balance.

Given India’s breakneck speed of growth, India’s regulators have not had the luxury for waiting for its general data protection law. Perhaps, as a consequence, India’s numerous regulatory interventions in the space have not had the smoothest journey. For instance, in April 2018, the Reserve Bank of India introduced a requirement to store payment data locally,[12] violation of which led to a ban on two of the world’s key card networks.[13] In the end though, India has demonstrated its will to stay the regulatory course, until the bans were removed after the underlying issues were addressed.[14]

Today, India sees a range of localization requirements in its regulations pertaining to securities market,[15] insurance,[16] telecom,[17] and direct selling.[18]

It is in this context that the old Section [17] threw up a storm. Of the more than 20,000 submissions and more than two dozen consultations[19] which reportedly accompanied the journey from the Draft to the Act, several, including those in which we were involved, dealt with the thorny issue of localization.

Perhaps consequently, while much of the Act resembles the Draft, it adopts a markedly different position on data localization from that of the Draft.

In effect, Section 16 of the Act enables the transfer of personal data by a Data Fiduciary[20] to any unrestricted country.[21] Interestingly, unlike the Draft, the Act does not specifically state that the countries will be notified after assessment of factors that may be considered necessary by the Government and the transfer will be subject to safeguards that will be spelt out in rules that can be notified later. However, it is possible that the safeguards may still be prescribed in the notifications under Section 16 of the Act. Some of these safeguards may also be prescribed as additional obligations on ‘significant’ Data Fiduciaries,[22] or be adopted voluntarily by organisations in compliance with the requirements to implement technical and organisational measures to ensure effective observance of the Act,[23] or to ensure compliance by data processors.[24]

While there is presently no indication of what such safeguards could be, some surmise on their nature is possible. Given that international data adequacy decisions, and ensuring predictability for global businesses is a key enabler of India’s avowed purpose of improving ease of doing business[25], it is likely that these measures could possibly take the shape of:

- A specific consent requirement for cross border transfers;

- Some form of data adequacy or equivalence requirement; and

- Either in combination with, or as an alternative to the above, some form of “private” protection for transferred data such as standard contractual clauses or schemes/ binding corporate rules.

The first of these requirements, if not read into existing consent or notice requirements under the Act[26] may stand out in contrast to the current position under the Information Technology Act, 2000 which mandates specific consent for transfers of ‘sensitive personal data or information’.[27]

The latter two requirements may be driven by imperatives of economics and geo-politics.

Of these, data adequacy (and its close companion, reciprocity) is a key point for existing trade negotiations[28], while private protections such as standard contractual clauses are likely going to become a necessary measure to enable transfers to countries where the relevant regulatory environment is not as secure.

The above being said, if predictability, and minimizing business disruption were key imperatives for the significant movement from the prohibitory tone of the Draft, to the far more facilitative and liberalized, approach of the Act, this outcome may be said to have been safely achieved.

Conflicting Imperatives

Much was made in policy circles about how the Draft was intended to have overriding effect, and how it would override (and therefore liberalize) data flows which were restricted under various localization regimes in India.[29]

This may be seen in retrospect as a bit of an own goal as the Act tries to remove all ambiguity, and states that it will not restrict applicability of any law which “provides for a higher degree of protection for or restriction on transfer of personal data” by a Data Fiduciary outside India.[30] For instance, will a different recommendatory regime, say, the EHR Standards[31] which provide for removal of patient identifying information or anonymization, qualify as higher degree of protection and restrict transfers that do not follow these recommendations?

In any event, by enabling stricter laws on data protection to prevail with respect to cross-border data sharing, what becomes clear is the intent of the Act, i.e., to provide only a baseline level of protection, while leaving enough space for sectoral regulators to come up with stronger safeguards as may be required.

[1] The Digital Personal Data Protection Bill, 2022 (“Draft”), available here.

[2] Section 2(t), Act: “personal data” means any data about an individual who is identifiable by or in relation to such data.

[3] Section 29(2), Draft.

[4] Reserve Bank of India, Notification, Storage of Payment System Data, RBI/2017-18/153 (“Localization Circular”), available here.

[5] The Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 (“Act”), available here.

[6] Article 40, Personal Information Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China, 2021, available here; Article 37, PRC Cyber Security Law, 2017, available here. See also, The Economic Times, China: Everything you should know about the Great Firewall of China – Massive censorship network, August 1, 2017, available here.

[7] Russia Federal Law No. 152-FZ of July 27, 2006 on Personal Data, available here. See also Erica Fraser, Data Localisation and the Balkanisation of the Internet, Scripted: A Journal Of Law, Technology & Society, Volume 13, Issue 3, December 2016, available here.

[8] See Frontier Economics, The Extent and Impact of Data Localisation, Report prepared for DCMS, page 108, June 01, 2022, available here; GSMA, Cross-Border Data Flows: The impact of data localisation on IoT, January 2021, available here; UNCTAD, Data Protection Regulations and International Data Flows: Implications for Trade and Development, page 4, 2016, available here.

[9] Data Protection Commissioner v. Facebook Ireland Limited, Maximillian Schrems (C-311/18) (the Schrems II case), the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU), July 16, 2020, where CJEU upheld the validity of standard contractual clauses while striking down EU-US Privacy Shield; Maximillian Schrems v. Data Protection Commissioner (Case C‑362/14), the Court of Justice of

the European Union (CJEU), October 06, 2015, where CJEU ruled that the European Commission’s adequacy determination for the U.S.-EU Safe Harbor Framework was invalid.

[10] European Commission adopted its adequacy decision for the EU-U.S. Data Privacy Framework, see Data Protection: European Commission adopts new adequacy decision for safe and trusted

EU-US data flows, European Commission, July 10, 2023, available here.

[11] European Commission, Standard contractual sections for international transfers, June 04, 2021, available here.

[12] Localization Circular.

[13] Reuters, India bans Mastercard from issuing new cards in data storage row, July 14, 2021, available here; Firstpost, Explained: Why American Express was banned in India for 16 months, August 25, 2022, available here.

[14] Reserve Bank of India, Press Release, Reserve Bank of India lifts the business restrictions imposed on American Express Banking Corp, August 24, 2022, available here; Indian Express, RBI lifts new card ban on Mastercard, June 17, 2022, available here.

[15] Principle 6, Framework for Adoption of Cloud Services by SEBI Regulated Entities (REs), SEBI, March 06, 2023.

[16] Regulation 18 of the IRDAI (Outsourcing of Activities by Indian Insurers) Regulations, 2017 (available here), mandates that all original policyholder records continue to be maintained in India;

Regulation 3(9) of IRDAI (Maintenance of Insurance Records) Regulations, 2015 (available here), insurers are required to ensure that the records pertaining to policies issued and claims made in

India (including the records held in electronic form) are held in data centres located and maintained in India.

[17] Section 39.23(viii) of the Unified License (available here) requires the licensee to not transfer any accounting information relating to subscriber (except for international roaming/Acting) and any

user information (except relating to foreign subscribers using Indian Operator’s network while roaming and IPLC subscribers), outside India.

[18] Rule 5 of Consumer Protection (Direct Selling) Rules, 2021 (available here) stipulates the obligations of the direct selling entities. The obligations include the requirement to store sensitive personal data within the jurisdiction of India, in accordance with the applicable law for the time being in force.

[19] The Hindu, Cabinet clears Data Protection Act, July 05, 2023, available here.

[20] Section 2(i), Act: “Data Fiduciary” means any person who alone or in conjunction with other persons determines the purpose and means of processing of personal data.

[21] Section 16, Act.

[22] Section 10(2)(c)(iii), Act.

[23] Section 8(4), Act.

[24] Section 8(1), Act.

[25] Money Control, Data Draft Bill tries to balance ease of doing business, privacy and national security: Jaishankar, November 29, 2022, available here.

[26] Sections 6, 7, Act.

[27] Rule 7, Information Technology (Reasonable security practices and procedures and sensitive personal data or information) Rules, 2011 (“SPDI Rules”). See also, Article 49(1), GDPR, and Regulations 10(2) and 10 (3), Personal Data Protection Regulations 2021 (available

here) read with Section 26 of the Personal Data Protection Act 2012 (Singapore), available here.

[28] World Trade Organization, Negotiation documents, available here; Centre for Law & Policy Research, India’s Engagement with Global Trade Regimes on Cross-Border Data Flows, available here.

[29] See generally, MediaNama, How Will The Data Protection Bill Approach Personal Data Transfers Outside Of India? #NAMA, December 17, 2022, available here.

[30] Section 16(2), Act.

[31] Electronic Health Record (“EHR”) Standards For India 2016, Standards Set Recommendations v2.0, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, December 30, 2016, page 21.

(credits and origin at https://corporate.cyrilamarchandblogs.com/2023/08/a-fine-balancethe-dpda-and-data-localization/)

Member Login

Member Login